Calls Before Echoes

Most field recordings of bat echolocation calls come with reflections from various surfaces, including the ground. However, the direct call arrives first, followed by the corresponding echoes. Here, we explore the primary analysis of echolocation call recordings obtained in the field condition.

Analyses on field recordings commonly employ a peak detection technique with some threshold to ignore the next n samples so that the next detection point is outside the same call. An example MATLAB® code is here:

[signal, fs] = audioread('rec.wav');

% Find peaks at least 0.01 in Y-axis, hold off until 10 ms length of samples until finding the next peak

[peaks, locs] = findpeaks(signal, 'MinPeakHeight', 0.01, 'MinPeakDistance', 0.01*fs);

% Visulaise detected peaks

plot(signal)

hold on

plot(locs, peaks, 'k*');

title("Detected Peaks");

subtitle(["Total Peaks = " num2str(length(peaks))]);

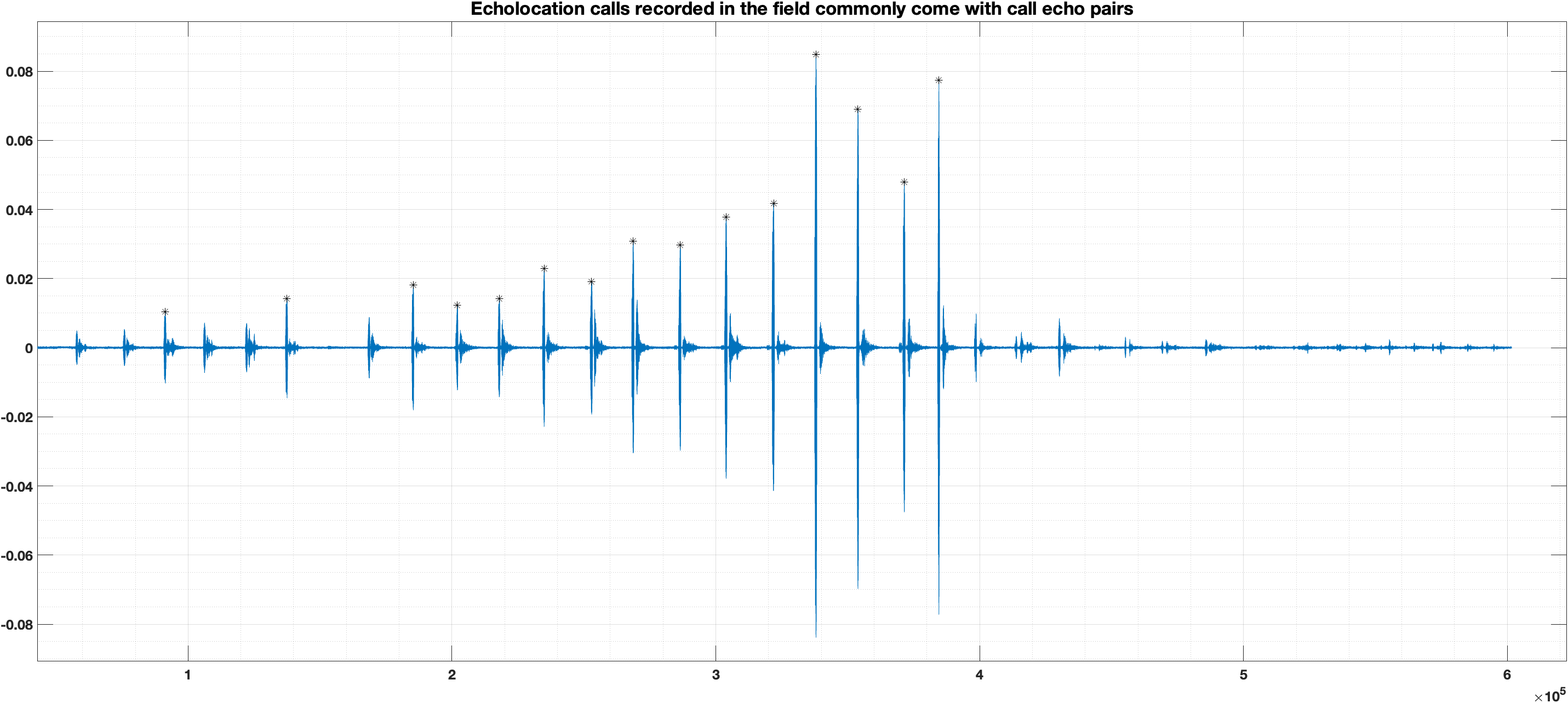

An example call recording with detected peaks is shown below. The X-axis is in samples. The sampling rate was 192kHz.

The peak detection method used in this example is crude, missing out on peaks below the threshold. Moreover, this technique requires knowledge of expected inter-pulse intervals. The more elaborate method will be described in a later post for automation of analysis of large datasets. Let us take a closer look at the recording now. Zoom into the plot and notice the details hidden in the waveform.

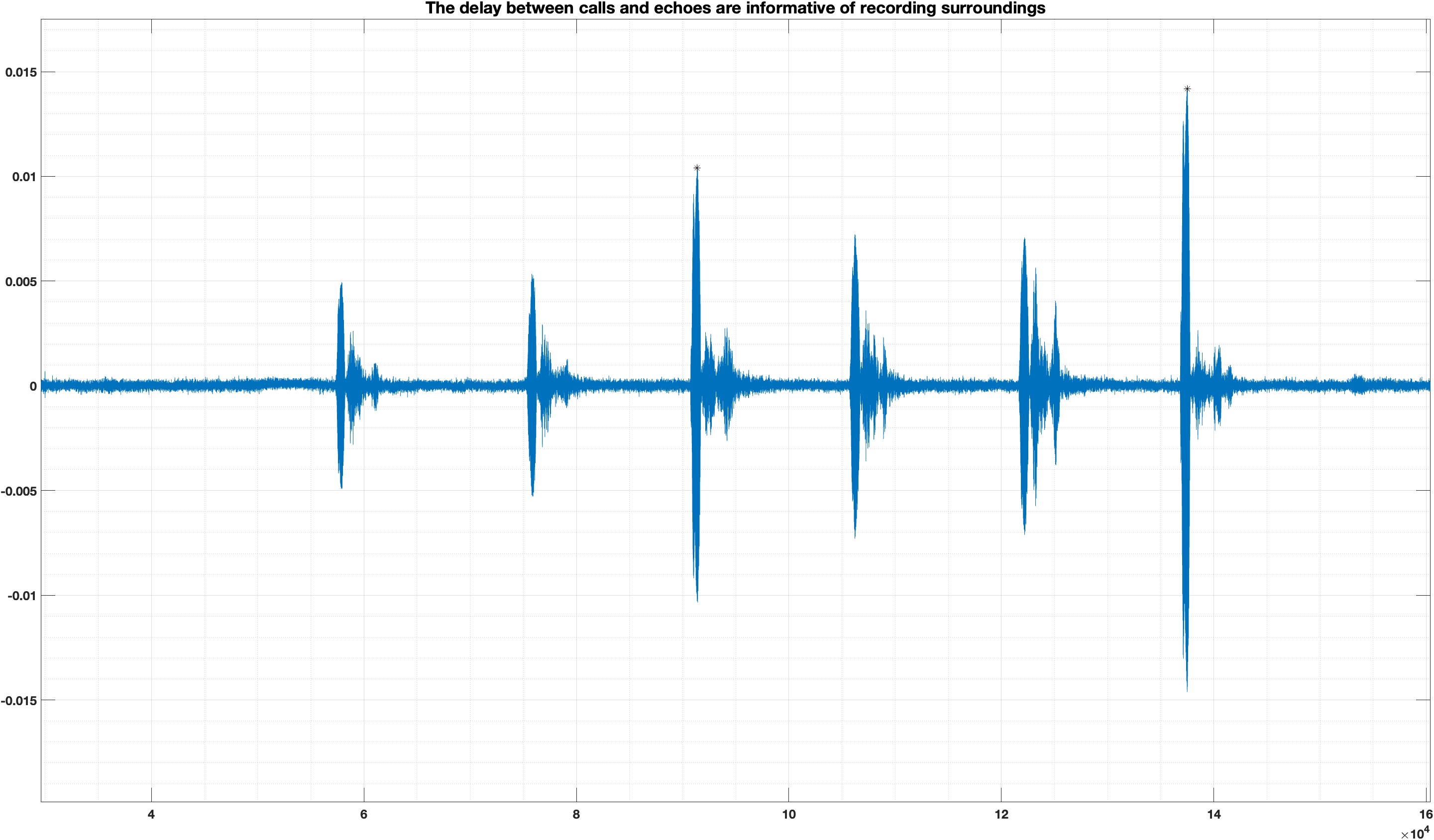

The distance - in samples - between the call and the echo gives information about the nature of the surroundings and possibly the flying behaviour of the bat. In the top image, the first call has the echoes follow very tightly. The fifth call in the same image has prominent double echoes, as do many other calls in the sequence.

You may use the function below to calculate the distance, in meters, based on two selected peaks, i.e., call peak and echo peak.

% Calculate the distance to a sound reflector using two detected peaks in a sound signal.

function path_difference = calculatePathDifference(peak1, peak2, fs, c)

% peak1, peak2 - obtain from k = ginput(2);

% fs - sampling frequency

% c - speed of sound in air, at STP, unless parameters known

path_difference = (abs(diff([peak1 peak2]))*fs)*c; % in meters

For a simple case analysis, assume you are standing with a wall on your right, holding a microphone parallel to the wall and the ground, and a bat approaching you from the front. The recording will contain direct calls and reflections from the wall and the ground, similar to the example above. As the bat flies right over you, the calls reach the microphone much earlier than the echoes.

Therefore, the delay between the calls and echoes varies due to the changing path difference between the direct and reflected paths.

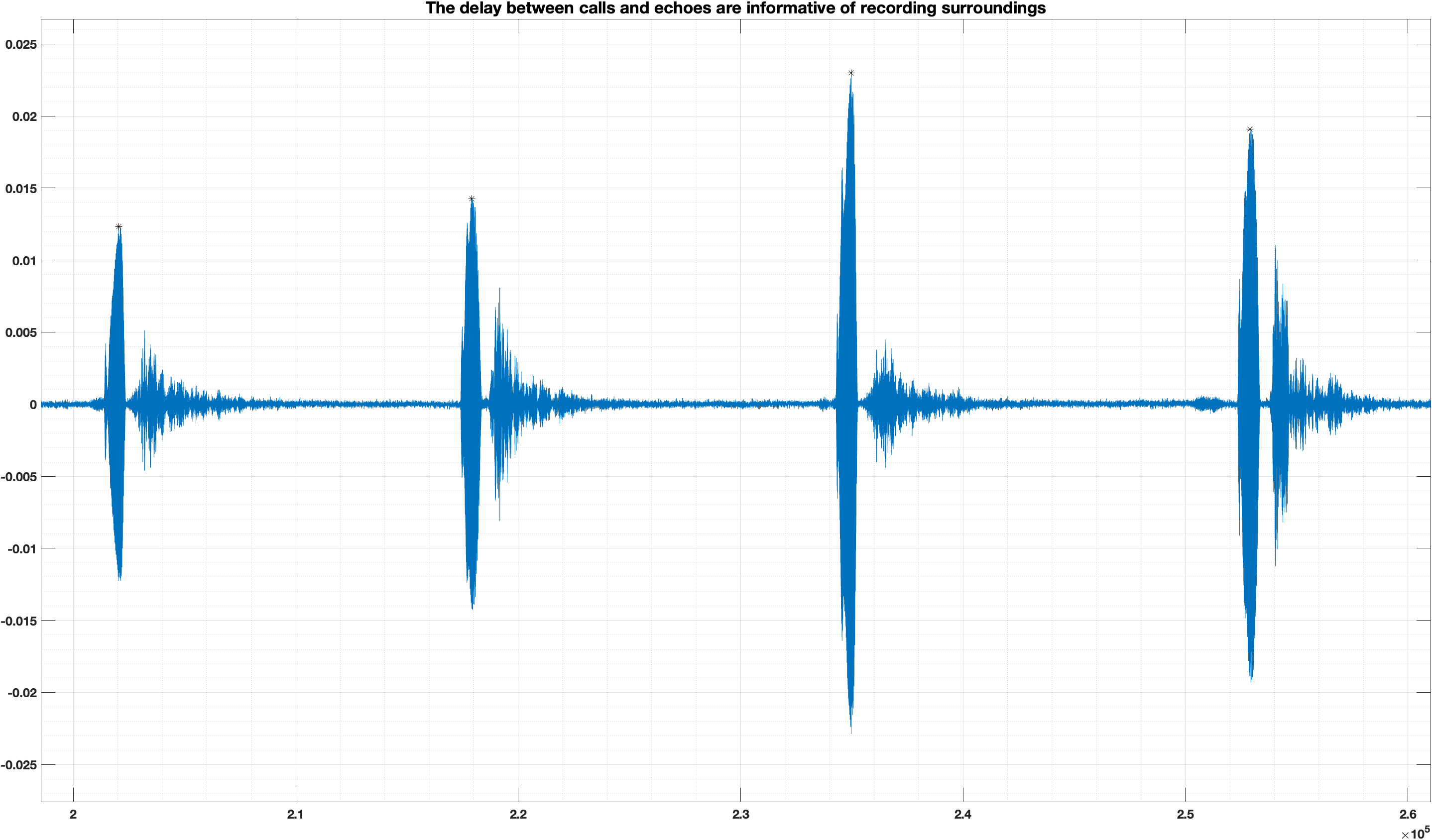

When the bat is very close to the microphone, the distance to the reflector would be overestimated by about twice. This becomes apparent in the bottom image in the above panel.

The louder calls produce louder echoes. However, it does not always appear that way in the recording if you notice the 11th call in the - counted from the very first call that is not detected by findpeaks() - the ratio between the call and echo level as expected from the call before and after it does not hold. What happened?

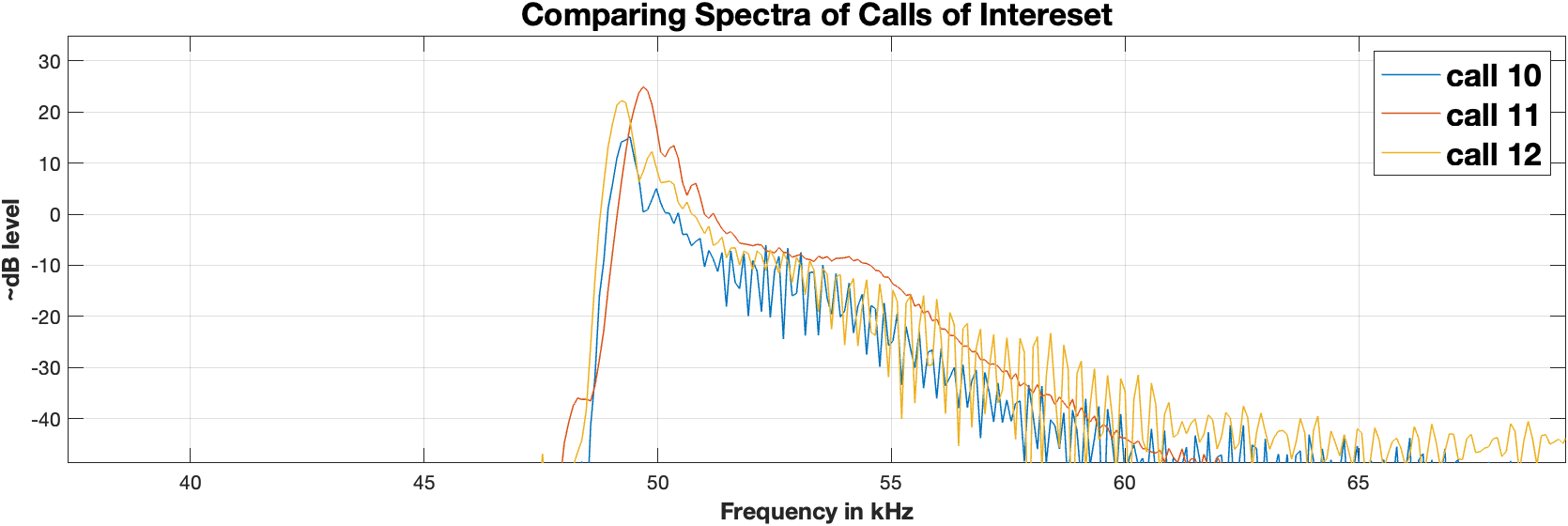

It is hard to know for sure. However, one distinct possibility is that this call was recorded more on-axis, hence the reduced echo strength. By on-axis, I also imply that the bat might have produced a more focused beam. The comparison of call spectra might reveal something.

There is a small upshift in the peak frequency of the call 11! The spectral peaks of the adjacent calls are almost the same. However, they have slightly different peak levels. The call of interest shows a shift in the peak frequency, providing weight to our speculation that the bat might have produced a more focused call - as the higher frequencies are more directed.

However, this is not conclusive. The bats do move their heads, and generally, the relative orientation of the bat varies as the bat flies.

As you may gather from this discussion, the echolocation behaviour of bats is complex and technically challenging to analyse, but that makes it all the more fun. The bat needs to rapidly adapt to changing acoustic scenarios. As I try to study the phenomenon, it is an endless wonderment for me.

You may download the example recording and try the analyses yourself.