The Making Of Esperdyne

Like many modern scientific disciplines, bioacoustics lives at the intersection of worlds. Physics meets biology; electronics meets behaviour; instrumentation meets sensory ecology. For students trained primarily in biology, the physics of sound and the electronics required to measure it often feel like the steepest hills to climb. For someone entering bat echolocation research from scratch, that hill can feel daunting.

When I began working with bats around 2017, back home in India, I was lucky to carry a different starting toolkit. My training in engineering had introduced me early to electronics, instrumentation, applied physics, and the mathematics that ties them together. That background helped me grasp, at least formally, what it means for a bat to perceive an echo. But understanding the equations is one thing; appreciating the depth of echolocation as a biological sensing system came much later—only after I immersed myself in the science of how bats actually use sound to interrogate the world.

Growing up in a tropical country means growing up surrounded by biodiversity. With even a little encouragement to be curious, the impulse to ask why is never far away. One of my earliest and most vivid memories is the daily emergence of flying foxes just after sunset—an enormous, living river of wings flowing across the sky. It happens almost everywhere in India, year-round. Fruit bats are conspicuous and familiar. The smaller echolocating bats, however, tend to surprise people—often triggering fear rather than fascination.

I remember a line from a story I read as a child: we fear what we do not know; knowledge helps quell fear. It stuck with me.

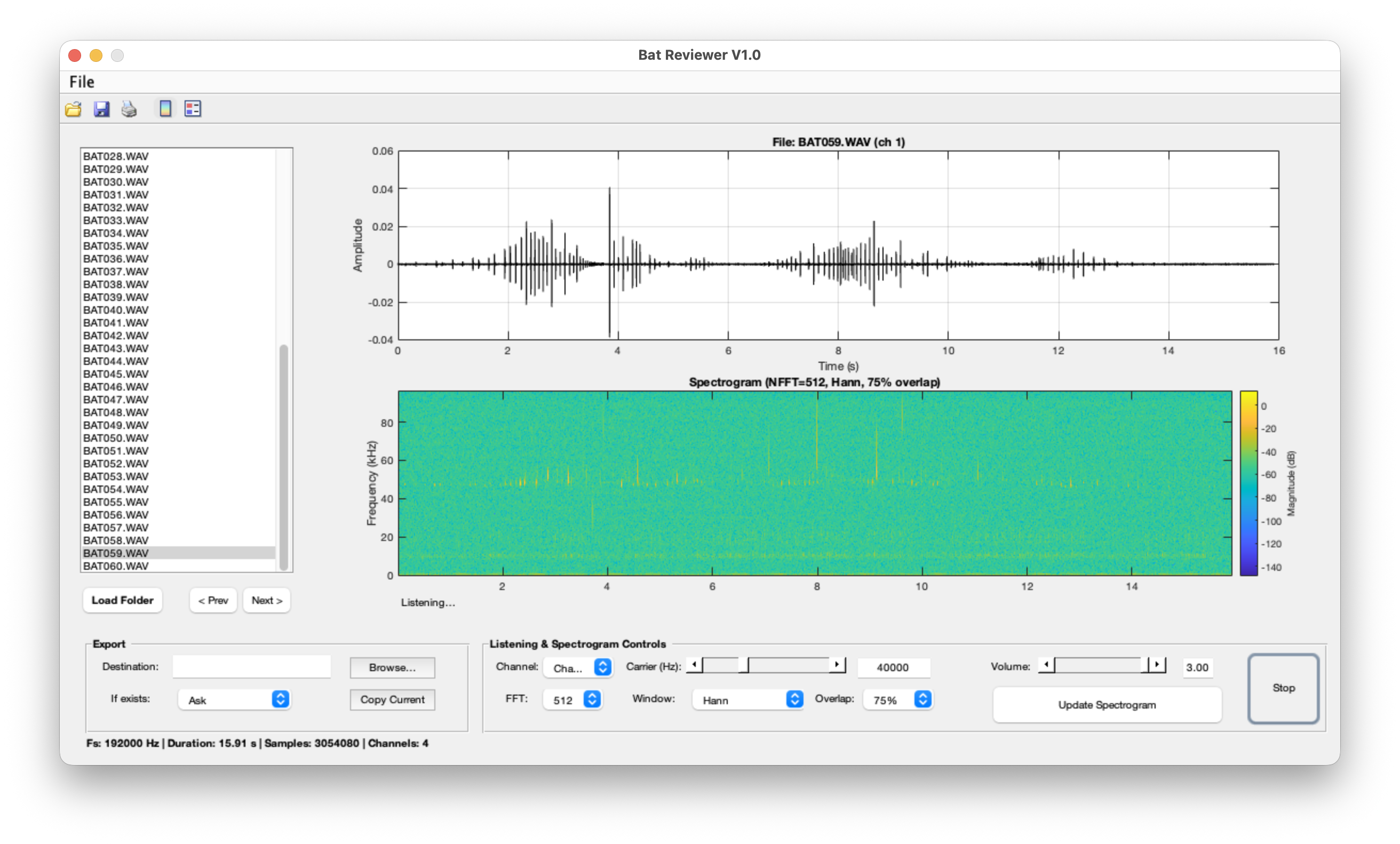

There is something profoundly unsettling about a world we cannot sense. Even when surrounded by flying bats, our ears are completely insensitive to the intense ultrasonic calls they produce. We are deaf to one of the most fascinating sensory behaviours in nature. And once you hear those calls—once ultrasound is translated into sound—everything changes. The invisible becomes tangible.

Hearing the Unheard

Detecting bats, whether for casual exploration or scientific research, requires specialised instruments—the bat detectors. At their core, these devices are frequency converters. Much like a radio, they translate signals from one frequency range into another—shifting ultrasound down into the audible domain. One common approach is heterodyning, a technique that has existed for decades and is well established in bioacoustics.

Commercial bat detectors have been available for a long time. They are no longer bulky, but they remain expensive, primarily because they serve a niche market. For students, early-career researchers, and conservation practitioners—especially outside well-funded institutions—this cost barrier is very real.

At the same time, the landscape of electronics has quietly transformed.

Advances in miniature electronics have made it possible to re-imagine scientific instruments from the ground up. MEMS microphones, powerful microcontrollers, high-speed data storage, and low-power displays can now fit on hardware smaller than a palm. Since the launch of the Arduino platform in 2005, access to these components has exploded. Platforms like the ESP series from Espressif, along with STM, Raspberry Pi, and countless other microcontroller families, offer an almost overwhelming range of possibilities.

For nearly any idea, there are multiple viable hardware paths—and, crucially, a vast maker community that actively develops and shares open-source designs, firmware, and tutorials.

From Maker Culture to Scientific Tools

The maker community has become an essential ecosystem for building cost-effective scientific instruments. Open electronics are no longer limited to hobbyists; they are increasingly embraced by professional scientists, particularly in fields where customised tools enable new methods or perspectives.

Esperdyne emerged directly from this ecosystem.

My personal motivation for developing Esperdyne as an open-source, low-cost bat detector and recorder—along with the broader journey behind it—is featured in a Methods Blog post:

That piece focuses on where it all started. What follows here is more about how Esperdyne took shape and what it taught me along the way.

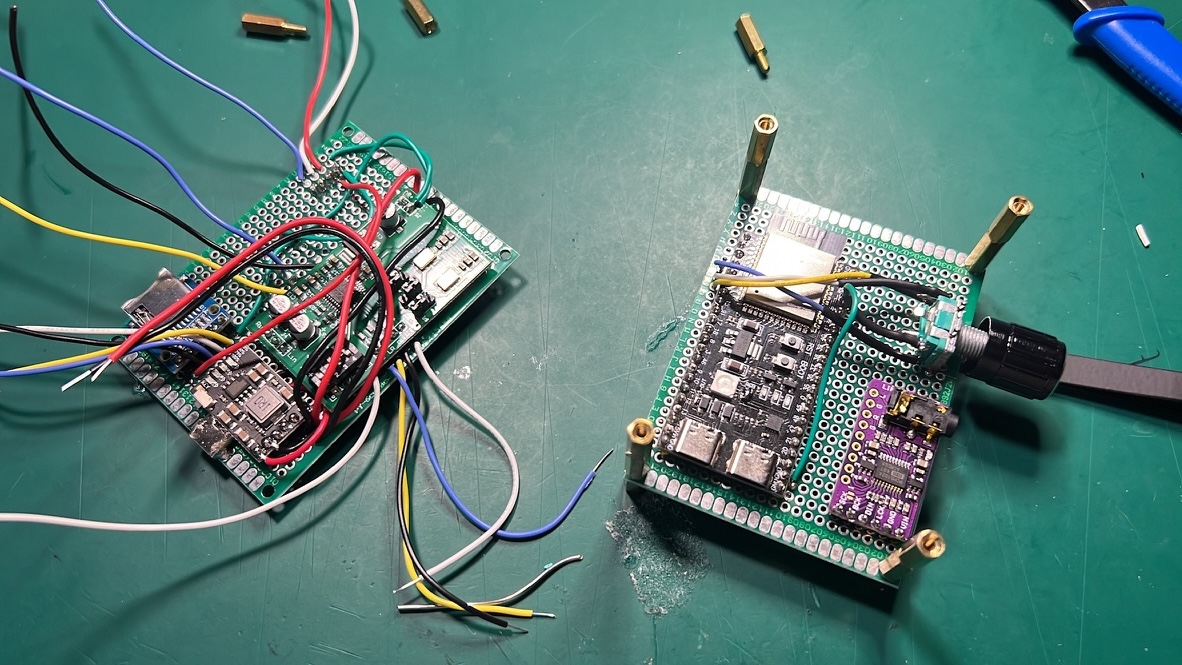

Building Esperdyne

Everything needed to build the device—code, hardware design files, documentation—is publicly available. In principle, anyone can assemble, modify, and adapt the system. In practice, it still requires effort, patience, and a willingness to try. For someone who has never touched a hobby electronics project, the learning curve can feel steep.

Community forums, open repositories, and especially video tutorials are invaluable resources. They lower the barrier just enough to enable experimentation.

I hope that others will take this project further, adapting it in ways I never anticipated. One idea I keep coming back to is a fully integrated headphone-based design: bat detection, heterodyne output, and recording built directly into a wearable form factor–with a single button to save the contents of the ring buffer to the SD card, enabling completely hands-free bat surveys.

Esperdyne in the Making

Pursuing this project was, above all, a long lesson in persistence. From the first rough attempts in 2022 to the final soldered wire in July 2025, the number of problems solved likely runs into the hundreds—accompanied by at least twice as many failures.

The journey was slow, often tedious, and frequently uncertain. Yet it was rewarding at every step.

Why keep going without knowing whether it would work? What makes someone return after the first hundred failures? Why build something from scratch when commercial alternatives exist? And after investing so much time and personal resources—why make it freely available?

There is not a single, neat answer. What I learned, more than anything else, is the value of continuing to work despite uncertainty. That is academic life in a nutshell.

Tools, Data, and Conservation

It is almost cliché to say that tools advance science — but they do!

What we cannot sense or measure, we cannot appreciate.

For me, the bigger picture has always mattered more than short-term gains. Imagine if every aspiring bat researcher, conservation student, or field ecologist had access to affordable ultrasound detectors and recorders. The implications extend far beyond academic research.

Bats remain underappreciated and widely misunderstood—often feared rather than valued. They are sometimes viewed as nuisances, particularly in historic or archaeological sites. At the same time, they face mounting threats: habitat destruction, light pollution, rapid urbanisation, and large-scale development projects. Conservation decisions increasingly depend on data collected by people on the ground, who document, analyse, and present evidence.

In the case of bats, a recorder goes a long way. It empowers those brave field scientists of conservation who work nights, often unnoticed, building the datasets that shape policy and protect ecosystems.

In the end, the joy of building Esperdyne was gratifying. There is no greater satisfaction than knowing that something you created proves to be helpful to others.

That, for me, is reason enough to keep building…